Slowly but surely, Peter Norman is finally being recognised as the hero he deserves – and always wanted – to be.

About time, too. It’s only taken half a century.

Tuesday marked 50 years since Norman claimed silver in the men’s 200-metre final at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City.

His time of 20.06 seconds still stands as an Australian record, would’ve won him gold at the Sydney Olympics and was part of the most successful Olympics from an Australian athletics team in history.

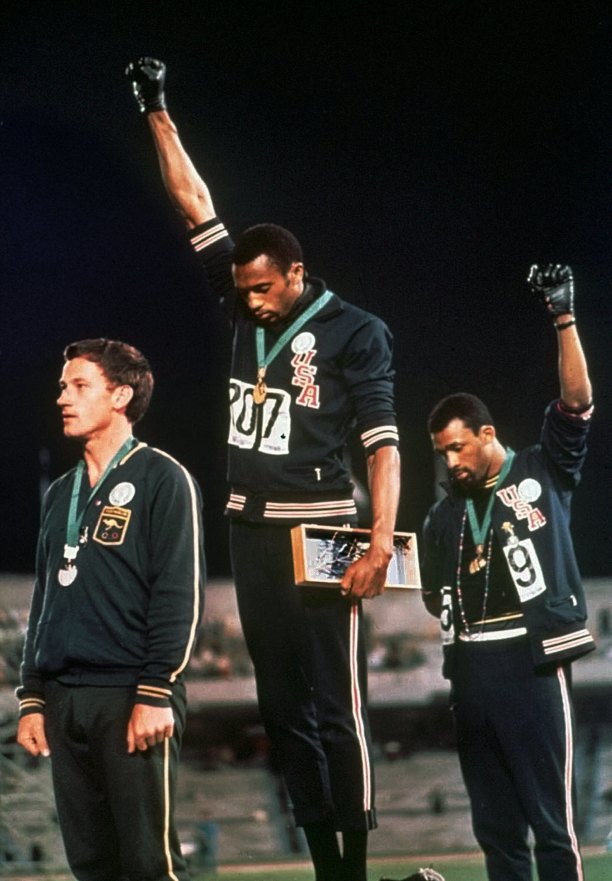

What Norman is widely remembered for, though, is the role he played in the silent protest of American sprinters Tommie Smith, who won gold, and John Carlos, the bronze medallist.

Time magazine considers it the most iconic photograph ever taken: the two black sprinters raising a fist, both sheathed in black gloves, into the thin Mexico City air as the American national anthem was played.

Smith and Carlos were protesting against the treatment of African Americans in their own country, at a time when the US was literally burning as the civil rights movement gathered pace.

Eventually, with time, Smith and Carlos became the legendary figures they deserved to be, even attending the White House with the American Olympic team after the Rio Games two years ago at the invitation of then-president Barack Obama.

Both of them dragged Norman's legacy along with them, especially after his sudden death from a heart attack in 2006. Carlos, in particular, mentions Norman at every opportunity. “God picked the right man,” he has said.

In America, Norman is just as attached to what happened in 1968 as Smith and Carlos. Australia has taken a little longer.

Earlier this year, the Australian Olympic Committee posthumously awarded Norman the Order of Merit. Earlier this month, Athletics Australia and the Victorian Government announced it would be erecting a bronze statue outside Lakeside Stadium in Melbourne. It will also adopt October 9 as Peter Norman Day, which has been celebrated in the US since his death 12 years ago.

It follows the apology in federal parliament in 2012 from Labor MP Andrew Leigh for his mistreatment by Olympic and athletics officials ...

Point of order, Mr Speaker!

Just how much Norman was blackballed, blacklisted, ostracised or just straight out wronged depends on who you speak to.

Last week, a book I wrote about Norman was released by publisher Pan Macmillan. What had started as an exciting project developed into a very complex story about a very complex – and very flawed – man.

There have been so many mistruths and lies told about Norman’s life that it took a lot of work to separate fact from fiction. The silliest was the claim he would’ve been given a paid job with the organising committee at the Sydney Olympics if he publicly condemned Smith and Carlos for the stance they took.

Unravelling other parts of his story was more problematic.

The one mostly disputed is whether he was banned from competing at the Munich Olympics in 1972 because of what happened four years earlier. It’s a question that will never be answered: the accounts vary wildly with each person (who is still alive) that you interview. Other athletes from that time, including Raelene Boyle, do not believe it cost him.

Since the book’s release, it’s been interesting to read and hear many of the mistruths raised again.

The assumption I came to in the end was that Norman was mostly hurt by being forgotten on the ladder of history. He thought he deserved greater recognition. And he did.

For mine, the most compelling – and overlooked – part of Norman’s story is how much the fame of 1968 completely threw his life off balance.

“There’s two Peter Normans,” said his former East Melbourne Harriers teammate Gary Holdsworth, who asked Norman to be best man at his wedding. “The story about what happened that night [in 1968] grew. Peter grew with it, around it, above it.”

Says Peter’s first wife, Ruth: “He came home and was a different person. Our lives weren’t our own any more. He’d become everyone else’s person.”

In the final stages of writing the book, Ruth and Norman’s children from that marriage – Janita, Sandy and Gary – agreed to be interviewed.

Sitting around a dining room table in Echuca, they laid bare their anguish and hurt about him walking out on the family to take up a relationship with another woman who he’d been having an affair with.

Ruth had to take Norman to court to squeeze maintenance payments out of him and, for many years, he refused to see his children. They reconnected with him later in life, but it was far too late. He died at the age of 64.

Each time they hear and read about their father’s deeds in 1968, it reminds them of their own personal tragedy.

“We are here, caught up in the legacy,” Janita said during our interview. “A lot of people have suffered in a lot of different ways. But there has to be a bigger picture.”

At Norman’s funeral, Janita placed a letter in his coffin.

“I told him I forgave him,” she said. “Because the importance of what Peter did that night means more than our hurt.”

Peter Norman, the flawed hero we are only starting to truly know and understand.