When the Olympic Games were last held in Tokyo, American multi-millionaire Avery Brundage was President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

He held office for 20 years and is widely regarded as the most controversial IOC President ever. Even in his lifetime, many were convinced that he harboured racist and anti-Semitic attitudes. As early as 1948, Life magazine talked of his “widespread unpopularity.”

His life has been brought into sharp focus after the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco decided to move a bust which had stood in the foyer of the building since 1972. Surprisingly, it admitted it had only become aware of Brundage’s controversial past in 2016.

Brundage had spent the majority of his adult life in Chicago, but had agreed to donate much of his collection to San Francisco back in 1959. On the condition that a museum was built to house it.

In all, some 7,770 pieces from the Brundage collection were put on display shortly before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. He later lost many others in a fire which swept through the mansion he owned in California.

Brundage had been an enthusiastic collector for much of his life. After attending one exhibition, he joked, "I came away so enamoured with Chinese art, that I’ve been broke ever since."

By the late 1930s, and already a successful businessman, Brundage visited Japan. He was welcomed by his IOC colleague Michimasa Soyeshima.

As his collection grew, Allen Guttmann, author of a major biography described Brundage as "The ideal customer! A millionaire in love."

When Brundage returned to Tokyo for the 1958 IOC session, he visited art museums in the company of sports officials and took the art specialists to watch sport.

"Undoubtedly the East has gained from its association with the West in the Olympic Movement and its adoption of Western methods of physical training, in stronger and healthier people. But, what about the West? Well, if the East gains in a physical sense, perhaps the West will gain intellectually and spiritually," he said.

Another IOC colleague, the East German publisher Heinz Schöbel, produced "the four dimensions of Avery Brundage." This was an impressive volume depicting Brundage the collector alongside his work as an Olympic statesman.

He had been an Olympic athlete in 1912. At the University of Illinois, he was a star performer on the athletics field whilst earning a degree in civil engineering. He was chosen for the United States Olympic team and paid his own way to Sweden for the Games. In the pentathlon, he finished fifth behind his illustrious compatriot Jim Thorpe. It was to be his best Olympic result.

Brundage proved very successful in business and was soon able to devote much of his spare time to sports administration. He sat on the US Olympic team selection committee for the 1920 Antwerp Games as representative of the Intercollegiate Conference Athletic Association.

Soon he was President of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) and in 1928 American Olympic Association (AOA) President.

Already he was forging a reputation as a fierce defender of the strict amateur codes in Olympic sport. Double Olympic gold medallist Mildred 'Babe' Didrikson fell foul of his strict application of the code. She had appeared in an advertisement without permission and was stripped of her amateur status despite the fact that she had not received payment. It was not a decision based on gender as he had already waged a war of words against 1920 Olympic 100 metres champion Charley Paddock, who had dared to criticise the committee.

Brundage was thrust into the international spotlight as the 1936 Olympics in Berlin drew ever nearer. There were calls by many to boycott them as a protest against the persecution of Jewish citizens and other minorities by the Nazi regime.

In 1935, Brundage was sent to Germany to evaluate the situation on the ground.

"I was given positive assurance in writing that there will be no discrimination against Jews. You can’t ask for more than that and I think the guarantee will be fulfilled," he said and remained a fierce opponent of any boycott.

Commodore Lee Jahncke, one of two incumbent IOC members in the US, held the opposite view which enraged the other members of the Olympic family.

IOC members "objected strongly to the attitude of Mr. Lee Jahncke in view of the fact that he had clearly infringed upon the Status of the International Olympic Committee in betraying the interests of the Committee and in failing to preserve a sense of decorum toward his colleagues."

Jahncke’s expulsion was confirmed in Berlin, where Brundage was welcomed to the fold.

Even so, the American team was beset by controversy. Star swimmer Eleanor Holm was thrown off the team for what Brundage described as "continued excessive drinking and insubordination, despite repeated warnings."

Later many questioned the decision to omit two Jewish sprinters, Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller, from the 4x100m relay. They were the only members of the US team who did not have the chance to run. It was true that the replacements were Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, but most had expected the US to win in any case. There were accusations that it had been done "because of their religion." Brundage denounced the reports as "absurd".

In an official AOA report of the Games, Brundage wrote: "Too much credit cannot be given to the Organizing Committee which, with the assistance of the German authorities, provided for the Games.

"These Games of the Xlth Olympiad of the modern cycle were unquestionably the largest and most magnificent yet held. Once more it was shown that keen contests, fairly held on the field of sport, promote mutual respect, not hatred."

In October 1936, at Madison Square Garden in New York, he told a meeting of the pro-Nazi German American Bund: "We can learn much from Germany."

On its release, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia official film of the Berlin Games had been banned from public exhibition in the US. Brundage and arranged private screenings and wrote, "unfortunately the theatres and moving picture companies are almost all owned by Jews."

Although war clouds gathered, he refused to accept that sport might have to cease.

He joined the Citizens Keep America out of War committee and when it became clear that the 1940 Olympics were impossible, he travelled to Buenos Aires to discuss the establishment of Pan American Games. These were scheduled for Buenos Aires in early 1942. After the Pearl Harbor attack, these too proved impossible. When they finally did take place in 1951, Brundage stood alongside Argentina’s dictator Juan Perón at the Opening Ceremony.

Brundage was by now IOC vice-president, even closer to the throne. During the war, IOC President Henri Baillet-Latour died and 71-year-old Sigfrid Edström of Sweden had taken over the leadership with support from Brundage.

In 1952, Brundage ran for the Presidency against the British peer Lord Burghley, later known as the Marquess of Exeter. Brundage polled 30 votes against 17 for his rival "amidst the general applause of the assembly."

Brundage did not officially take office until September 1 1952, but at the Session in Helsinki, he spoke about China and Germany, two major problems for the Olympic Movement throughout his tenure. His own relationship with mainland China did not help. After the Communist takeover, he was persona non grata in Beijing. Throughout the 1950s, there was open hostility in his communications with their representatives.

Brundage’s correspondence files also included complaints from the Israeli Olympic Committee.

They had been excluded from the 1955 Mediterranean Games in Barcelona at the insistence of Arab nations. Brundage insisted "we cannot become involved in a matter of this kind." Even so, Games organisers were still permitted to fly the Olympic Flag.

Brundage did enjoy some successes. From the mid 1950s until the late 1960s, the two Germanies competed under a tricolour emblazoned with the Olympic rings.

"Another example of an important victory for sport over politics," he hailed. "The spectacle of East and West German athletes in the same uniform, marching behind the same leaders and the same flag is an inspiration under present political conditions and a great service to all the German people who wish for a united country."

Even so, his autocratic style often antagonised. He was nicknamed 'Slavery Bondage' for his strict enforcement of amateur regulations.

He was twice challenged for the IOC leadership and it is almost unheard of for an incumbent President to face such a challenge. His opponent was the Marquess of Exeter, who did not succeed, but the challenges were emblematic of discontent among individual National Olympic Committees (NOCs) and International Federations who suspected correctly that he did not value their opinions.

The distinguished journalist David Miller described Brundage as a "despotic moralistic bulldozer".

Even Brundage was apparently aware of his own capacity to polarize. In a "note to self" discovered by his biographer Guttmann, he had written: "AB, clever fellow, Imperialist, Fascist, Capitalist, Nazi and now Communist."

From 1960, the South African problem took centre stage. Sixty-nine died after police opened fire at Sharpeville, a township in the Transvaal some 67 kilometres from Johannesburg. Although South Africa did take part in Rome 1960, it proved the last time for a generation.

Many African nations were now independent. Their sporting influence grew with the foundation of a Supreme Council for Sport in Africa (SCSA) which demanded the expulsion of South Africa.

Brundage dispatched a commission of enquiry to visit the Republic. He described it as a "delicate and important task" and wrote to Lord Killanin who was to lead the group.

"If we are to judge apartheid per se, it is not for us to send a commission at all. Our concern is with the NOC and what it is doing to comply with the Olympic regulations."

Brundage insisted the situation was "analogous" to 1936 in Berlin. And told Killanin "we must not become involved in political issues nor permit the Olympic Games to be used as a tool or a weapon for an extraneous cause."

The group met Prime Minister John Vorster, leaders of the South African National Olympic Committee (SANOC) and representatives of anti-apartheid groups.

They concluded that SANOC’s proposals were "an acceptable basis for a multiracial team to the Mexican Games."

It was the Olympic equivalent of Admiral Horatio Nelson putting the telescope to his blind eye to avoid seeing orders he did not wish to see.

The SCSA threatened a boycott of Mexico 1968, supported by the Soviet bloc. The IOC voted 47-16 to reverse its decision and South Africa were left on the outside. Brundage called it "a sad commentary on the state of the world today."

In 1968, the civil rights movement in the US was also at its height. Brundage had written to Mexico organisers warning them to avoid any occurrences that "will endanger the dignity of the Games."

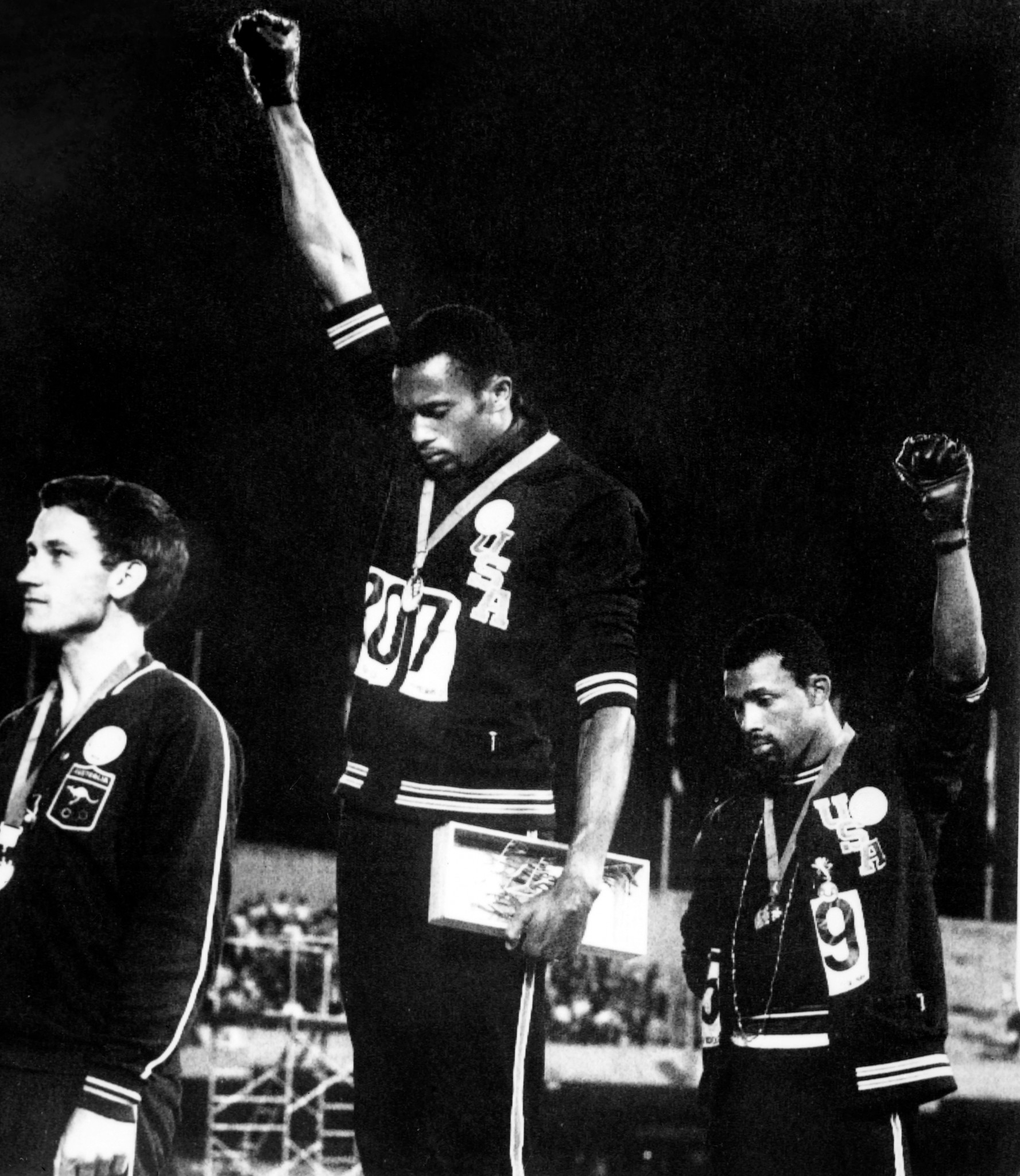

At the 200m medal ceremony, American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood alongside Australia’s Peter Norman in the most famous podium protest.

Brundage exerted pressure on the United States Olympic Committee and the pair were expelled from the Games for violating "basic standards of good manners and sportsmanship."

When the official film of the Games was released, footage of the demonstration was included. Brundage wrote to Mexico 1968 organising chief Pedro Ramírez Vázquez to try and censor the images. "It was very disturbing to have you confirm rumours about the use of pictures of the nasty demonstration against the United States flag by negroes in the official film of the Games of the XIX Olympiad."

Brundage went on, "it had nothing to do with sport, it was a shameful abuse of hospitality and has no more place in the film than the gunfire at Tlatelolco".

At least 300 students had died when Government forces opened fire on a demonstration in the square at Tlatelolco before the Games.

Despite Brundage’s anger, the sequence was retained.

In 1972, approaching his 85th birthday, he decided, or was persuaded to stand down.

He did not go quietly. He forced the expulsion of Austrian skier Karl Schranz from the Sapporo Winter Olympics to make an example of what he considered the commercialisation of the Games.

Effigies of Brundage were burnt in Austria when the decision was announced.

"Brundage had his black list" Schranz later told insidethegames. "He could not afford to kick out the French in Grenoble 1968, but he could afford to get rid of me in 1972 because we were a small nation."

Schranz said he had tried to talk to Brundage, who had told him curtly "we do not talk to individuals."

The Munich Games were fast approaching and with them another crisis.

Rhodesia had made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) and wanted to compete as "Rhodesia". They had been banned from Mexico 1968 because they did not have United Nations recognition.

In 1972, Brundage’s IOC ruled that they could compete provided they did so under their colonial name "Southern Rhodesia". At that time, the country had discriminatory policies based on ethnicity.

At the Village welcoming ceremony, the Southern Rhodesia flag was raised to God Save the Queen.

Many suspected that this was window dressing, especially when Rhodesian team manager Ossie Plaskitt told the media "we are ready to participate under any flag, be it the flag of the Boy Scouts or the Moscow flag, but everyone knows very well that we are Rhodesians."

The SCSA called for a boycott if the Rhodesians were allowed to take part and the IOC was again forced to rescind the invitation.

In the meantime, everything was overshadowed by a terrorist attack on the Israeli quarters in the Village which Brundage described later as a "brutal assault".

Although Lord Killanin had been elected as the new IOC President, Brundage remained in office until the end of the Games. He was criticised for his attempts to manage the crisis which ended in tragedy when the Israeli hostages were all killed.

A day of mourning was declared and Brundage spoke at the hastily arranged memorial ceremony in the Olympic Stadium.

"Every civilised person recoils in horror at the barbarous criminal intrusion of terrorists into peaceful Olympic precincts."

Then came the most controversial part of his speech.

"The Games of the XXth Olympiad have been subject to two savage attacks. We lost the Rhodesian battle against naked political blackmail. I am sure the public will agree we cannot allow a handful of terrorists to destroy this nucleus of international cooperation and goodwill."

Many were angry at the insensitivity shown by mentioning the Rhodesian affair in the same breath as the massacre.

He then famously insisted: "The Games must go on."

Brundage’s Olympic journey came to an end shortly afterwards but now, 45 years after his death, his legacy seems destined for further scrutiny.