A childhood encounter with a touring steelband began Stephen Stuempfle’s connection with Trinidad. Now the US scholar has written an illuminating history of Port of Spain in the era before Independence. As Judy Raymond learns, Stuempfle’s research has only deepened his love for T&T’s capital

In the twilight, wild deer tiptoe between the trees outside Stephen Stuempfle’s suburban home in Bloomington, not far from the sprawling, equally leafy campus of the Indiana University, where he works as an administrator with the Society of ethnomusicologists.

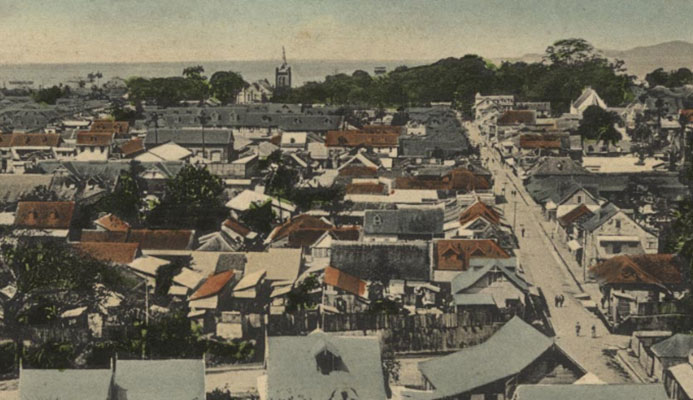

But in his head, Stuempfle walks the streets of Port of Spain. He’s written a book about the city, published in April by the University of the West Indies Press: Port of Spain: The Construction of a Caribbean City, 1888–1962. Almost five hundred pages long, it covers the period from Trinidad’s cocoa boom to Independence, an era that stretched, he explains, from “the height of British power at the turn of the twentieth century through decolonisation.” Thus Port of Spain’s evolution into a modern capital city “was interrelated, both practically and symbolically, with the building of a society and a new nation-state.”

Though Stuempfle is an academic — and he does include some theorising about cities and development — this book is hugely readable. It’s a compilation of deliciously detailed portraits of the people, areas, buildings, and events that featured in Port of Spain’s growth and change in that period, such as the American army taking over King George V Park as a camp in the Second World War, and the campaign promoting the ultra-modern building materials (reinforced concrete, aluminium louvres, and tiled floors!) of Diamond Vale to lure house-buyers to this spanking-new dormitory suburb. All these vivid minutiae are set against the social and political events of the day that led to them.

Stuempfle records, for instance, how engaged the people of Port of Spain were with plans for a war memorial, eventually erected in 1924. First came a debate — from 1916 — over placing it downtown on Broadway or uptown in the “Little Savannah” (the latter won out; it’s now Memorial Park). Then there were squabbles over whether a black sentry (from the West India Regiment) or white (from the Merchants’ and Planters’ Contingent) should be posted at a more prominent corner for the unveiling (the latter almost refused to turn up at all if not given pride of place, but eventually conceded). Later there was ardent discussion of whether citizens should salute or lift their hats as they passed: the inhabitants, of all classes, were enormously proud of the memorial.

Stuempfle resurrects the forgotten career of architect Herbert Brinsley, who changed the city as dramatically as George Brown before him and Colin Laird afterwards. Brinsley, who flourished in the 1930s, designed the Globe Cinema, a new hall for Bishop Anstey High School, the Neal and Massy Garage, the Alston Building, the Treasury Building, the Electricity Board’s transfer station at Frederick and Park Streets, and many houses. The stories of Queen’s Hall, the city’s cinemas, the Art Deco renovation of the Queen’s Park Hotel, the deep-water harbour, the city corporation’s 1914 silver jubilee celebrations — Stuempfle tells all with a zeal that makes them fascinating.

He himself knows Port of Spain well: he lived in Calcutta Street, in the city’s western St James district, from 1987, while researching his PhD thesis on steelpan. He enjoyed the liveliness of the neighbourhood, “from the late-night food on the Western Main Road to the annual observance of Hosay.” He got around by taxi, careful to learn the protocols: “I worked hard to gain competence as a taxi passenger: learning the names of spots along the road, knowing when to request a drop (not too soon, not too late), and understanding when to proffer payment (depending on the size of your bill and other factors).” He also met his future wife, Denise, during his eighteen months in Trinidad, and though they live in the US, they return regularly to visit family and friends.

Stuempfle’s first, indirect encounter with Trinidad came much earlier, through steelpan: when he was about ten, Tripoli came to perform in his home town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Though not particularly musically talented himself, he was fascinated. He later began visiting Brooklyn for the Labour Day Carnival, did a course in the folklore department of the University of Pennsylvania that included Caribbean music, and discovered that Tobagonian folklorist and anthropologist J.D. Elder had done his doctorate on Trinidadian music there. Stuempfle himself studied the social dynamics and symbolism of pan; a version of his doctoral thesis was published in 1995 as The Steelband Movement: The Forging of a National Art in Trinidad and Tobago. In what reads now like a harbinger of this new book, it begins with an affectionate description of Laventille Hill and its view over the city, in the days when Desperadoes’ panyard was still perched near the summit, and the panmen — once regarded as badjohns themselves — hadn’t yet fled their own territory for fear of gang-related crime.

That book is more academic than this one, though Stuempfle was a curator at the Historical Museum of Southern Florida in Miami for over a decade, and has been at Indiana University since 2008: it’s the headquarters of the Society for Ethnomusicology, of which he is an administrator.

But Port of Spain, though scholarly, is a labour of love. Stuempfle began researching it (in his own time and at his own expense) in 2005. At that time, the city was changing rapidly, and “like many people, I was astonished by the disappearance of large portions of the built environment. I then tried to figure out how to write a book that would capture something of the city’s unique geography, architecture, and way of life.”

During his earlier sojourn in Trinidad, Stuempfle had spent time in panyards, gone to steelband events, and interviewed panmen. The years of work on this book entailed walking the city streets taking photos, as well as documentary research at the National Archives, the University of the West Indies, and the National Library. Military sources at the US National Archives and the New York Public Library enriched his account of how the Americans commandeered large chunks of the capital, as well as the better-remembered airbases in northeast Trinidad and the naval base at the northwestern peninsula of Chaguaramas. He draws extensively, too, on local newspapers and on fiction by V.S. Naipaul, Samuel Selvon, and Ralph de Boissière, as well as nineteenth-century visitors such as Anthony Trollope and Charles Kingsley.

Stuempfle began writing in 2012, making time for this private passion alongside his job on campus. His next project is on an even grander scale: “a study of general patterns in Trinidad’s basic landscapes, including forests, plantations, villages, and towns,” and examining, as he did with the capital city, how its people regarded and shaped their environments during the twentieth century.

The most surprising part of his research, he says, was the “rhetoric of progress . . . shared by people of very different socioeconomic backgrounds and political views. Many people believed they could improve themselves in the city and also improve the city itself,” he found. “There was a strong sense of civic consciousness and pride.”

That optimism is also the most surprising thing about the book. Although not a native, Stuempfle shares much of its past inhabitants’ feeling about the city — probably more than many of those who live or work in it now, or the conservationists close to despair over successive governments’ indifference to the city’s and the country’s built heritage. Many of the buildings Stuempfle writes about have been torn down or merely ignored to the point where they collapse from sheer neglect; his book is, inadvertently, a memorial to many. Yet he still sees Port of Spain as “a city of extraordinary cultural vitality,” and writes of it with an undaunted, infectious enthusiasm.

His own favourite area is Belmont, in the nineteenth century the home of free Africans, and later a respectable working-class district. Stuempfle admires “its long history of community-building and its dense landscape of houses and narrow streets, which helps foster social interaction. Also, my wife grew up there during the 1950s and 1960s, and I love listening to her stories about her home on Erthig Road, the neighbourhood families, the local shops, and the Carnival masquerades.”

He also “greatly appreciates” the Botanic Gardens, established over two hundred years ago by Governor Sir Ralph Woodford, once a source of great pride, and even now quietly cherished. “The gardens’ botanists and caretakers do excellent work,” he says — perhaps overstating the case a little — and adding, significantly, “the grounds remain the quietest place in Port of Spain.”

Stuempfle retains his touching faith in the city’s people and the theory that, sometimes consciously, sometimes not, they shaped Port of Spain to suit their needs and desires. That view of its history also extends to its future. His own love of the city, he says, “continues to deepen the more I learn about it,” although he understands why living in it year-round can be stressful (he doesn’t list the reasons, such as crime, potholes, lack of parking space, traffic, inadequate drainage, an erratic water supply . . . the list can seem endless). Stuempfle even believes Port of Spain’s future is brighter than its past.

“The goodwill and resourcefulness of the city’s inhabitants,” he says, “will eventually prevail over the violence and destructiveness.”