The International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced new guidelines on Thursday that ban athletes from making political, religious and ethnic demonstrations at the upcoming 2020 Summer Olympic Games in Tokyo.

The Olympics “are not and must never be a platform to advance political or any other divisive ends,” said IOC President Thomas Bach. “Our political neutrality is undermined whenever organizations or individuals attempt to use the Olympic Games as a stage for their own agendas, as legitimate as they may be.”

While Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter already prohibited athletes from protesting at the Games, it did not give much clarity on what counts as “protest.” The new guidelines specify examples, including displaying political messaging in signs or armbands, kneeling, disrupting medal ceremonies or making political hand gestures.

The IOC announcement comes at a time when activism among athletes has surged amid rising political tensions, particularly in the United States. Last August, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee placed hammer thrower Gwen Berry and fencer Race Imboden on a year-long probation after kneeling during a medal ceremony at the Pan American Games in Lima Peru.

Several athletes have spoken out against the new guidelines, including soccer player Megan Rapinoe who wrote in an Instagram story: “so much being done about the protests. So little being done about what we are protesting about. We will not be silenced.”

Though the IOC is advocating for political neutrality, the Olympics have been a stage for political protests since the Games began in 1894. Here is a brief look at the history of protests.

At the 1906 Olympic Games in Athens, Irish track and field athlete Peter O’Connor carried out one of the first and most famous acts of political protest in Olympic history.

In 1906, O’Connor entered the games to represent Ireland. New rules implemented later that year, however, only allowed athletes nominated by an Olympic Committee to compete. Because Ireland did not have a committee at the time, the British Olympic Council claimed O’Connor as their own. When O’Connor, a proud Irishman, found out he would be competing for Great Britain, he was outraged. In 1906, the battle for Irish independence was in full swing and demands for constitutional change to allow for self-governance were growing.

In protest, O’Connor scaled a 20 foot flagpole in the stadium, waving a green flag with the words “Erin Go Bragh” (Ireland forever) while his co-athlete Con Leahy distracted Greek authorities.

While Olympic officials frowned upon O’Connor’s protest, he was never expelled or put on probation. He competed two days later and won gold in three competitions. After each win, O’Connor waved his green flag.

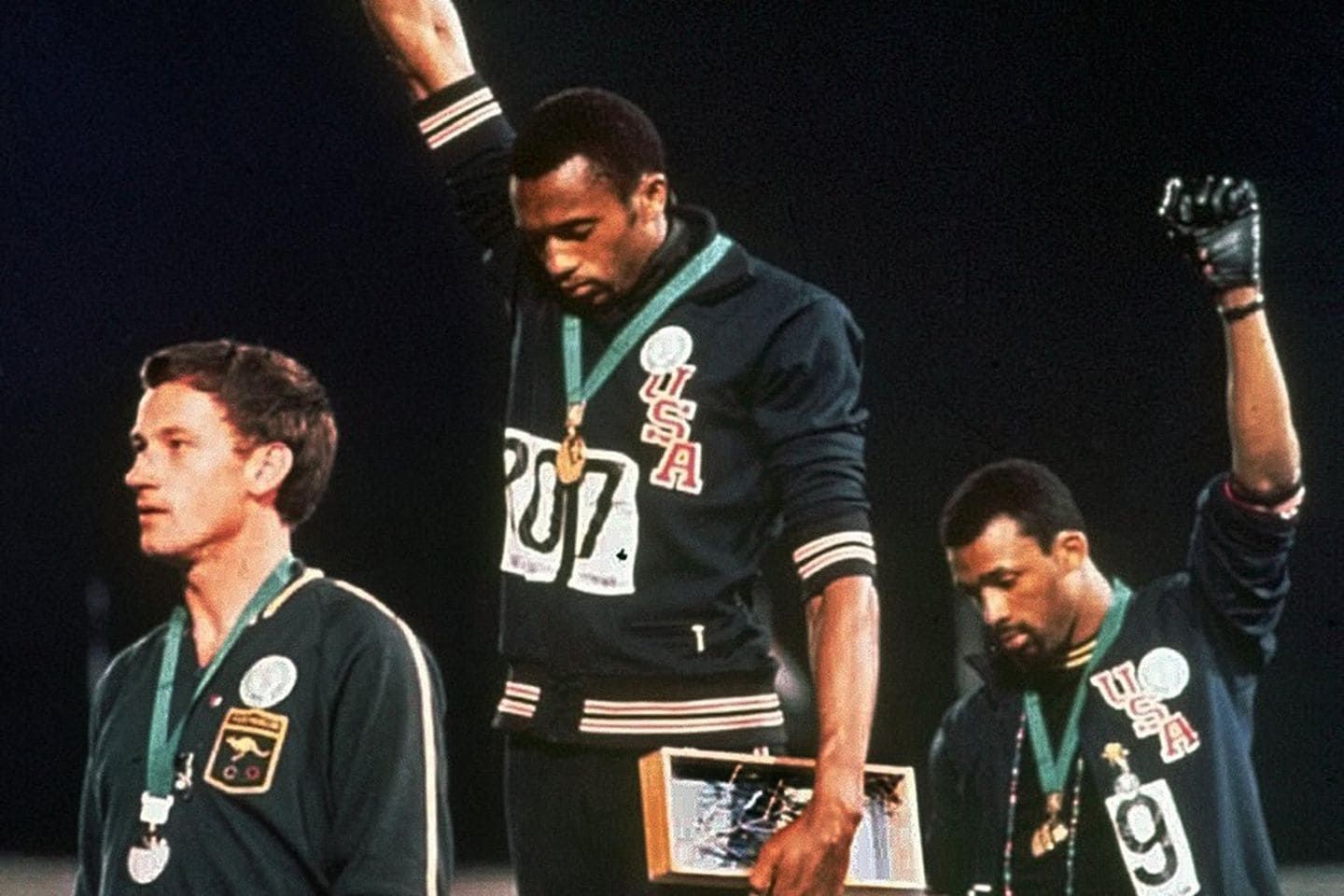

When American runners John Carlos and Tommie Smith stood on the medal podium to receive their respective bronze and gold medals at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968, they famously raised their fists in a Black Power salute when the American national anthem began playing. Their Australian co-medalist Peter Norman stood in solidarity with them, wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge during the ceremony.