By BASIL INCE

When the Trinidad and Tobago athletes returned last August from Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, site of the last Central American and Caribbean Games (CAC Games), they brought home their best results ever. They won 33 medals and finished eighth on the roster of 27 countries. They broke their previous record of 24 medals won 44 years ago and far outstripped the comparatively few medals won when they first attended the Games at Barranquilla, Colombia in 1946. The most interesting statistics germane to this article, however, are the number of medals won by our women. They won nine of the 12 track and field medals, garnering golds in track and field, cycling and hockey. Our women footballers also won silver. In the 1946 Games, no women represented Trinidad and Tobago.

Equally interesting was the number of disciplines in which our women competed, viz., badminton, basketball, football, hockey, squash, shooting, table tennis, track and field and volleyball. Furthermore, there were other sporting activities in which our women athletes were engaged. There were the Youth Olympic Games, the Commonwealth Games, a regional junior tennis tournament, a World Indoor Hockey Tournament, a cricket tour and the upcoming World Championships in netball. Several of the competitions are conducted among various age levels such as under 15, under 16, under 18 and under 20. This burst of activity raises the question of how to explain the overwhelming differences between the non-inclusion or the exclusion of women from selected teams to represent Trinidad and Tobago in high-level international sports competitions in the early days and what currently obtains. The thrust of this article suggests that socio-economic and political circumstances make the difference.

The CAC Games were not the first international games in which the country participated. We competed at the Commonwealth Games, then known as the British Empire Games, in 1934 in London. There was no woman competitor on a team which comprised only one athlete, Mannie Dookie. The CAC Games are regional in scope and are only larger than the CARIFTA Games which are confined to the Anglophone Caribbean countries. Held quadrennially like the Olympics, the Pan American and Commonwealth Games, the CAC Games usually happen two years before the Olympics.

Today, Trinidad and Tobago competes in four major games, the three previously mentioned and the World Championships which are confined to track and field and are not like the others in the multi-sport category. Women compete at all of these Games which are regarded as high-level international competitions. The country’s participation in international competitions spans two centuries—the 20th and the 21st. Two centuries or a span of 80 years are sufficient to witness socio-economic and political changes. Throughout this period, the country participated fairly regularly at international games. Since the nation made its debut at the Commonwealth Games in 1934, it attended all games save those of 1986. The nation sent its first team to the CAC Games in 1946 and has participated at these Games ever since. The country became eligible to participate from 1935 when the name of the games was changed from Central American Games to the CAC Games to allow for the inclusion of the Caribbean countries.

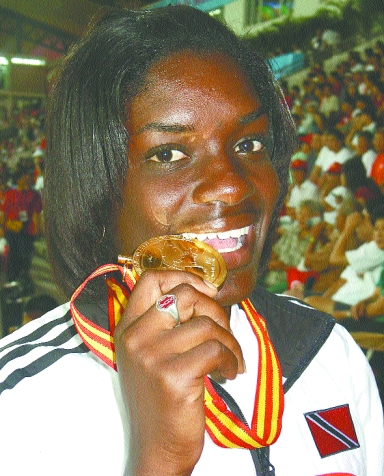

Rhonda Watkins

The nation’s participation in the Olympics and Pan American Games began in 1948 and 1951 respectively. The World Championships, staged for the first time in 1983 by the IAAF, are the last of the major games in which Trinidad and Tobago began to compete. The competition at these games differs in quality from the CAC Games because of their regional scope. Before 1983 and the advent of the World Championships, the Pan American Games were of a higher quality than the Commonwealth Games because at that time the United States , then the most powerful nation in the sprints, the area in which Trinidad and Tobago and the Caribbean states excel, participated.

After 1983, the United States opted to send second-tier athletes to the Pan Am Games and its top-rated athletes to the World Championships because their dates clashed. Today the quality of the Commonwealth Games may have surged slightly ahead of the Pan Am Games. There is no doubt, however, that the Olympics are the most prestigious of all the games with the World Championships a close second. Both are global in scope with the Olympics multi-sport in character while the Championships are confined to track and field. The medals won by Trinidad and Tobago at each games corroborate the pecking order; the higher the quality of the games, the fewer the medals won.

When Trinidad and Tobago began to compete on the international scene, it was a colony struggling to meet the expenses incurred in sending a team. When Mannie Dookie, for example, participated at the Commonwealth Games, he was sponsored by the Trinidad Guardian which performed a similar function for McDonald Bailey when he competed at the CAC Games in Barranquilla. In 1948, the Trinidad Olympic Committee committed itself to send a fourth athlete to the Olympics in 1948 “if funds are available.” When the country participated at the Games at Helsinki in 1952, shortage of funds was again an issue. The two weightlifters selected, Rodney Wilkes and Lennox Kilgour, were uncertain of travelling on the night before they left. It was only on the eve of their departure that the Legislative Council agreed to fund the trip.

Three years later, Trinidad and Tobago sent its largest team up to that time to the first Pan Am Games because the team was funded by the hosts, Argentina. The reason for the sponsorship was that the Argentine dictator, Juan Peron, wished to ensure the success of the inaugural hemispheric games. Space has been devoted to the lack of funds issue because it would later be advanced as the reason for the non-inclusion of women.

Financial constraints also had an impact on the method of travel. Today junior teams jet around the world to represent the country at a proliferation of meets. That was not the case of the 1938 Commonwealth Games team which had to make its way to Sydney in Australia by ship. The lengthy voyage affected all the athletes, including the team’s top sprinter, JRN Cumberbatch, who had problems training. On his arrival in Sydney, he was out of shape and ran out of contention. A year later, he won a bronze medal at the British AAA meet at White City. Sixteen years later when those Games were held in Vancouver, British Columbia, a star-studded team which included Olympic medallists Rodney Wilkes and Lennox Kilgour had an arduous journey to arrive at its destination.

They left Trinidad by a bauxite boat which rocked and rolled them to the eastern seaboard of Canada. On landing there, the team transferred to the train for its transcontinental trip to Vancouver in western Canada. This wreaked havoc with the team’s training plans since the athletes had to endure three or four days of inactivity. One competitor described water rushing through the portholes at midnight in the Atlantic .

According to Kilgour, an eventual silver medallist at the Games: “You came down and had lunch, watched the scenery through the glass of the train and you went up and slept.” In a sense, the team had a vague idea of what Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the American explorers, experienced during their first transcontinental trip from the East to the West coast on the North American continent.

In the games mentioned, the Commonwealth Games (1934, 1938, 1954), the CAC Games (1946), the Olympics (1948) and the Pan American Games (1951), there was not a single female representative on any team. Even if the men experienced difficulty making small teams and faced hassles in travel, those problems were non-existent for women. They were invisible as international sporting representatives for this country and their selection was a virtual non-issue. Several reasons accounted for this state of affairs.

When the modern Olympic Games were held in Greece for the first time in 1896, women were not included. Four years later in Paris, out of a total of 1118 competitors, there were only 21 or 1.9 % women representation. By the mid-twentieth century, however, when the Games were held in London (1948), women were 355 or 8.7 % of the 4064 competitors. At the first Games of the 21st Century held in Sydney, over 38% of the competitors were women who numbered 4070 out of a grand total of 10,650 competitors. The change in women’s participation at the Olympics from 0% near the end of the 19th century to 38% at the start of the 21st is breathtaking in the circumstances. The drastic change can be seen not only in the number of women participating but also in the number of events in which they participated. In 1896, there were no women’s events but by 2000, there were 135 events for women in addition to the 12 mixed events for both genders.

When the ancient Olympics began, they were open to men only. Women, however, were allowed to enter the precincts of the games only to cheer on the male competitors to victory. It was only later that women were allowed to participate. The modern Olympic Games followed the same pattern.

It was not until the second Olympics in Paris in 1900 that women competed in the modern games for the first time and then they were limited to competing in events such as croquet and tennis, sports considered ladylike and less demanding. The founder of the modern Olympics, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, was among those individuals who were adamantly opposed to women’s participation in sports which he considered too strenuous.

His argument ran thus: “Respect of the individual’s liberty requires that one should not interfere in private acts…but in public competition, (women’s) participation must be absolutely prohibited. It is indecent that the spectators should be exposed to the risk of seeing the body of a woman being smashed before their eyes. Besides, no matter how toughened a sports woman might be, her organism is not cut out to sustain certain shocks.”

The Baron was not singular in his outlook since many of his persuasion operated in the Victorian era which regarded sports as inimical to child bearing and as likely to make women less marriageable. Victorian thinking held that women were weak and helpless and that their place was in the home.

Involvement in sports, therefore, ran counter to marriage which was regarded as the acme of their aspirations. Snyder and Spreitzer put it this way: “For girls and women to participate in sports was contrary to the Victorian ideal. Sports would take a woman out of the home to engage in a rigorous activity. It would place a woman in a situation where her modesty might be compromised, where overall property could be endangered. It also feared that attracting a mate and childbearing could be hindered or prevented by injuries to the reproductive organs.”

Although Queen Victoria died early in the 20th century, this thinking persisted many years beyond her reign. Thus it was not until the Olympics at Amsterdam in 1928 that women were able to ‘graduate’ from tennis and crochet to track. By then, they had been allowed to compete in fencing, golf, gymnastics, swimming and diving. Their treatment was analogous to that of the crown colonies which the metropolitan power brought along slowly by bits and pieces until the eventual granting of independence.

In Trinidad and Tobago, the non-inclusion of women was the status quo when the nation’s first teams went to international games. Even much later on, two scholars could write that “the general position held by women in Caribbean societies is essentially subordinate and of secondary importance to men.” The scholars went on to note that West Indian women have not been socialized much differently from other women in the Western world and, as such, “support the traditional female role of wife, mother and homemaker.” Traditional thinking held sway in Trinidad and Tobago and helps to explain women’s absence from our early national teams. A contributing factor was that the women competitors were not up to scratch at that time.