BEFORE any amendment is made to Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) must firstly acknowledge the fact that this decree was built on the pillars of racial discrimination and inequality.

So says TT Olympic Committee (TTOC) president Brian Lewis who believes the creation and implementation of this specific guideline in 1975 came as a result of two acts of racial solidarity portrayed by four African American athletes at the 1968 (Mexico) and 1972 (Germany) Summer Olympics.

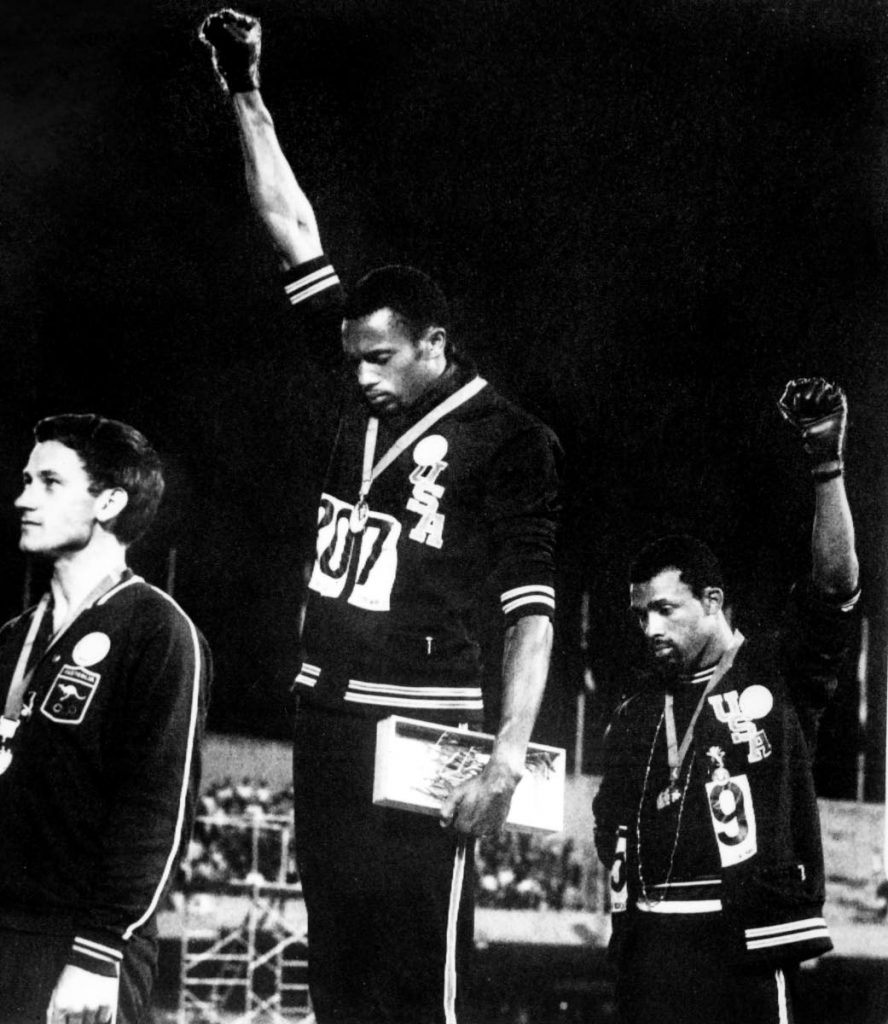

During the men’s 200m medal ceremony in Mexico City, gold and bronze medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos respectively, each raised a black-gloved fist during the playing of the US national anthem in protest of racial inequalities throughout the US.

Even white Australian silver medallist Peter Norman expressed empathy with the pair’s ideals by donning an Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) badge while atop the podium.

Four years later, in Munich, African American quarter-milers Vince Matthews and Wayne Collett sprinted to 400m gold and silver respectively. Both runners refused to stand at attention for the US national anthem and opted to stroke their beards and twirl their medals in salute of the struggles of African Americans.

These peaceful displays saw Matthews and Collett banned for life by then IOC president and fellow American Avery Brundage. Brundage was also at the helm of the global Olympic fraternity during Smith and Carlos’ historical “Black Power Salute.”

After the 1972 Games, Brundage completed his service as IOC head and is believed to have played an instrumental role in the constructing of Rule 50 three years later.

Rule 50 says, “No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.”

Since the murder of George Floyd and the meteoric rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in May, several multinational corporations, sporting bodies and other organisations have reassessed their operations and work ethic to ensure racial equality is observed.

Additionally, entities such as the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, US Olympic and Paralympic Committee Athletes’ Advisory Council (led by Carlos) among others and inclusive of the TTOC president have urged the IOC to scrap Rule 50 and replace it with new guidelines developed “in direct collaboration with independent, worldwide athlete representatives that protects athletes’ freedom of expression”.

Lewis also called for the reinstatement of Matthews and Collett, 48 years after the ban was put into effect, and the pair given the highest Olympic award – the Olympic Order – for their stance against injustice.

At the IOC executive board meeting, on July 15, president Thomas Bach said, “We see no reason to rewrite history in this moment.”

He added that the IOC’s Athletes’ Commission will still consult on the rule by saying, “The athletes have already multiple opportunities to express their views also during the Olympic Games – press conferences, mixed zones, social media, interviews, TV meetings and others. Rule 50 addresses only the field of play and the ceremonies.

“To reconcile these values of free expression on one hand and respect for each other on the other, the IOC Athletes’ Commission has initiated a dialogue among athletes on how they can even better express their support for Olympic values in a dignified and non-divisive way.”

However, in a recent article published by The Telegraph on Tuesday, Kirsty Coventry, who is leading the global consultation as chair of the IOC Athletes’ Commission says all options remain on the table.

According to Coventry, many athletes want taking a knee while competing at next year’s Tokyo Olympics to remain banned amid fears it could open the door for other forms of protest. Coventry says a decision will be made by the end of this year.

“What if we have three athletes all wanting to stand up and have three different protests or fight for three different things? That would not be ok. It would look awful. It’s supposed to be your Olympic moment when you’ve won a medal.

“Let’s say this rule gets changed, we allow for something and we have three different (protests). What do we then do? Who allows what? Who makes that decision? What does it look like? We can’t just change the rule to this, because if we do then it changes the rule for this, this and this,” said Coventry.

She also said the Athletes’ Commission could decide to implement some other form of group protest away from the podium.

In response to this string of events, Lewis believes the IOC should accept responsibility that Rule 50 was originally based on Brundage’s racial legacy.

He said, “There are different views and it’s important that all sides are heard it’s an important part of the process. I am aware that amongst the athletes there are different views. What is important is that the history of Rule 50 not be ignored. Rule 50 is explicitly linked to 1968 and 1972 and is a legacy of Avery Brundage.”

The TTOC boss continued, “Rule 50 has racial discrimination and inequalities as its foundation. Any review of Rule 50 must acknowledge that historical fact. It’s not a question of rewriting history...it’s already written. The ban on Vince Matthews and Wayne Collett has to be rescinded. Avery Brundage’s legacy and impact can’t be denied.

“I know there are people in the International sport movement who are hoping Black Lives Matter will be a temporary fad and talking point. To those who wish to diminish and marginalize this issue I say no way,” he concluded.